Artsy Mommy Issues: 2 Shows on Motherhood in the Crossfire

Both Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf and Galerie Gisela Clement in Bonn show exhibitions on motherhood. Let's compare.

Outlining the Field of Research

Where do we even start? It’s a strange time to make these shows. One in an institutional setting in Düsseldorf, another one in a commercial context in Bonn. Last year in Antwerp, I remember Gallery GNYP did a group show called Mary With(out) Child. I understand the criticism of such exhibitions: “Why are women reduced to their (hypothetical) ability to birth children?” Fair. These shows have weird timing. The 4B-Movement, “Incels” vs. voluntary celibacy, women opting out of dating in general, and a right wing push to put women “back” into the domestic sphere (only rich white women historically afforded to be stay-at-home-mothers, while women of all other demographics had to work outside of the home, so I doubt whether the idea of putting women “back into their place” is even historically accurate lol). So yeah, why are we pulling out this topic so prominently?

I don’t even want to go into who/what/how/why a mother is because otherwise we won’t get to the review. What I’d like to say though, is that fatherhood isn’t nearly as polarizing and discussed as motherhood is. Fatherhood doesn’t face as much scrutiny and isn’t in the public eye as much as motherhood is. It’s actually interesting that Ta-Nehisi Coates said, “Anyone can make a baby, but it takes a man to be a father” (a phrase that exists in a similar wording in German, too), while girls, no matter their age or preparedness, turn conceptually always into mothers. Strange, huh? Reminds me of the lawyer’s painfully true monologue in Marriage Story (2019).

Let’s have a look at the titles first, which already disclose differing attitudes. Kunstpalast’s MAMA is an intimate title of endearment, the title kids give their moms way before learning that they have names of their own. The subtitle From Mary to Merkel already includes religious and political role models. Moreover, it designates age range. Mother at Galerie Gisela Clement, however, is formal and distanced; it’s a descriptive term. It might go all the way into coldness and indifference. But Mother also makes me think of drag and its empowering connotation that made Mother reenter mainstream slang.

This is what we can expect from both shows: An emotional, relatable retelling of motherhood at Kunstpalast and a more formal approach at Galerie Gisela Clement. While Mother works exclusively with post-modern and contemporary art, MAMA includes historical artifacts to present broader cultural narratives of motherhood.

The Dive In

The Kunstpalast exhibition curated by Linda Conze, Westrey Page, and Anna Christina Schütz1 strongly emphasizes immersion with color concepts. The first room is pink. According to the introductory wall text, the exhibition addresses motherhood “[w]ith a focus on the Western world” but “open[s] up a panorama that concerns everyone.” Hm. The first object is a song: Mama, performed by Heintje from the movie To Hell with School (1955). The wall label assumes that everybody and their mom (lol) knows this song. I don’t. Feels like a nod to the generational demographic primarily addressed here. Around the corner, there’s three more Mama songs performed by Luciano Pavarotti, Ricky Martin, and Bärbel Wachholz. The label explains that the song was originally performed by Benjamino Gigli in the movie Mamma. Filmed in 1941 🚩. As an Italo-German cooperation 🚩🚩🚩. Yes, some beloved cultural traditions have their roots in fascism, and I’m glad that Kunstpalast addresses this fact. This might sound sarcastic now, but I’m actually disappointed that we didn’t start with Bohemian Rhapsody here.

A bit further, I see a video compilation of actors thanking their moms at the Oscars. I think it’s a telling curatorial choice: The show starts with the perspective of children on their mothers. Sure, they all say, "Thanks Mom for being so great." A feel-good moment for moms and kids walking through the exhibition, exchanging a hug and dwelling in wholesome early childhood memories. Cute! But the relationship isn’t inherently built on viewing the mother as a whole human being. It’s rather a relationship and emotional bond based on all the labor that the mother does for her child. And I think it’s strange not to say that part out loud.

Both shows deal with the religious iconography of motherhood through the figure of Mary, Mother of God, but I think that Kunstpalast is just overdoing it. After twelve Madonna sculptures, several Albrecht Dürer etchings, and more Baroque annunciation scenes, IT’S ENOUGH SLICES! Come on, at least add a scandalous Katharina Fritsch (Baby Boomer, German) sculpture of Mary in whore-yellow. Especially considering that the commentary on the labels wasn’t that critical of the religious doctrines implied in these representations. Like, you had Pietàs but not a single hortus conclusus depiction which insisted on virginity and isolation as womanly virtues?

Also, I really need to call out Kunstpalast on the half-assed commentary. It’s one thing to keep mediation accessible and the other to dumb it down. Simon Kick’s 17th-century painting Interior with a Lady, to Whom a Servant is Holding up a Mirror features the lady in question placing her hand on her prominent belly. The label now speculates whether she’s alluding to her pregnancy based on this sole detail. A questionable approach, given that in the 15th century, for example, dresses used to enhance the belly area to allude to fertility, not because a woman was actually pregnant. Such speculations were applied to Jan Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portait (1434) and disproved by historians. Sure, in the 17th century, fashion could have changed in this regard. But you’d need receipts to prove your point instead of looking at a century-old artwork through modern-day eyes.

Also, the curators chose to focus on the family representation depicted in the etching L’Heureux Ménage [The Happy Household] (after 1769) while ommitting any commentary on the French phrase written underneath: The wildest American, after a battle full of horrors, would be moved to tears by this image. But in our civilized countries, the feelings of nature, long eclipsed by the heart, exist only in painting. You know what’s actually wild? Keeping that undisclosed.

Like yeah, there were some very big names like Käthe Kollwitz, Barbara Kruger, Louise Bourgeois, and Alice Neel. Joëlle Dubois (Millennial, Belgian) and Vivian Greven (Millennial, German) did not necessarily have their best works featured. But I hoped for something more crushing, more daring, I felt like damn, give me Paula Rego’s abortion series, give me Tracy Emin, Nan Goldin, Mierle Laderman Ukeles and her care work performances. OMG: Imagine Gustave Courbet's L’Origine du Monde (1866) as a first piece and the folks clutching their pearls!

Mother in Bonn fills in the gaps that MAMA in Düsseldorf leaves open. I must admit that I didn’t see the complete show, given that it was restructured, so some works were missing. Louisa Clement’s (Millennial, German) candid-series consists of self-portraits, or more precisely, nude selfies. In the erotic framework, nudes are meant to be sent to a sexual partner, to show “what they’re missing out on” to maybe get an Adam Levine type reply like “Holy fucking fuck,” “That body of yours is absurd”. Instead, Louisa shoots pics that would be considered rather unflattering. Contrary to nudes, they don’t explicitly feature sexualized body parts. And the pixelated phone pic resolution mimics the blemishes of perfectly normal, imperfect skin.

Handling Controversy

To my surprise, Kunstpalast featured more subversive works than I would have expected. Leigh Ledare (Gen X, US-American) portrayed his ballerina-turned-porn actor mother over the years. Elina Brotherus (Gen X, Finnish) absolutely SLAYED with her Annonciation series. Annonciation 10 (2011) highlights the ambiguous reaction to finding out one’s pregnancy. A naked woman sits on a chair, looking down onto the tiled floor where pregnancy tests and a bowl lie. She is framed by the wall behind her, the tiles separating her head from her body. To the left, an open door leads into a dark corridor. To the right, a room with a photograph hanging on the wall: An unidentifiable dark silhouette. An allusion to violence? Was the pregnancy involuntary? Was what led to the pregnancy involuntary?

But my favorite part of Kunstpalast was probably Barbie’s pregnant friend, Midge (2004). Her husband Allan is just a paper cutout in her box. Damn, fathers aren’t even fully present parents when they are dolls!

In both shows, some works don’t refer to motherhood directly. Anna Oppermann’s colorful drawings in Bonn center the pelvic area. As an abstract separate entity, it gives me an uncanny feeling. It suddenly looks like nothing more than a reproductive space. In Düsseldorf, Martha Rosler’s video Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975) was an unexpected piece: The artist stands in a kitchen wearing an apron. She holds up kitchen tools and somberly names them. Before putting them back, she aggressively demonstrates how to use them, which gains a comic effect and simultaneously serves as a reminder to never mess with the person that has access to the knife cabinet. Although I love the piece, it demonstrates in the context of the show how hard it is to separate motherhood from the general expectations of womanhood.

Judith Samen (Gen X, German) was represented both in Bonn and Düsseldorf. In Bonn, I liked her work o.T. (Buesenschüssel) (1998) a lot. And I was incredibly happy to see Sanja Iveković (Baby Boomer, Croatian) in Bonn: In her Women's House (Sunglasses) (2002-4, ongoing) series, she uses real luxury label ads for sunglasses. On top of those posters, she adds the name of a woman, her age, nationality, marital status, and number of children. What these women have in common is that they’re real victims of domestic violence and abuse who fled their abusers. The sunglasses ads gain a cynical dimension, reminding me of women covering their bruises to keep up the image of a happy marriage.

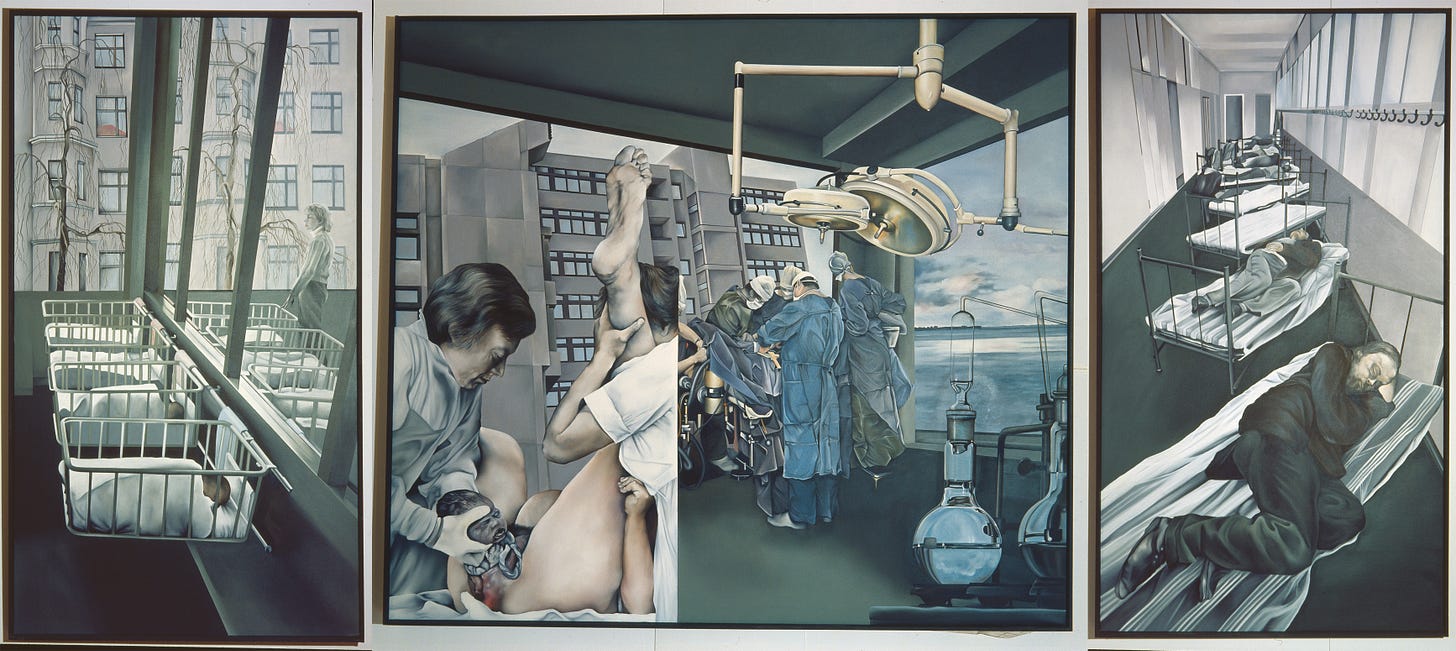

Annegret Soltau’s (Baby Boomer, German) schwanger SEIN [BEING pregnant] series (1977-78) highlights the identity-transforming notion of pregnancy. You don’t have a child. You become a mother. Along with photographic documentation of her performances while pregnant, Annegret deconstructs pregnancy and its personal and societal implications in diagrams, adding scientific distance to what is usually presented as a highly emotional and intimate phenomenon. Maina-Miriam Munsky (1943-99, German) at Kunstpalast, too, questions the intimacy and beauty of childbirth. Her triptych Westend (1977) is tinted blueish grey. Sickness and new life are on opposite sides of the altar-like piece. In the center, a woman gives birth, the child’s grey head finally peaking out looks nothing like the imagined miracle of life. The newborn station on the left is depicted looking down and tilted, the perspective and the mirror reflection adding a dizzying effect.

OMG I just remembered: You know what is the biggest missed opportunity at Kunstpalast? Given that they focused on a longer cultural history of motherhood, they could have displayed Valentine de Saint-Point’s Manifesto of the Futurist Woman (1912). The manifesto WRITTEN BY A WOMAN urges women to give birth so their sons can die in war. That could have been such a scary commentary on the current political climate. Instead, they gave us a picture of a woman holding up a “Hallo Mutti” [HI MOMMY] poster at the 2016 CDU Rally for Angela Merkel. That picture would be in the dictionary if I were to look up “anachronism”…

Both exhibitions feature works by men and hence male perspectives on motherhood. While I’m very critical of Kunstpalast’s limitation to Western perspectives, they do feature some PoC and Global South artists and interrogate how colonialism shaped motherhood. Renée Cox (Baby Boomer, US-American) recreated Mary holding her dead son as a Black mother, alluding to police brutality. Lebohang Kganye’s (Millennial, South-African) overlays family photographs with her own image, inserting herself into the memory of her late mother. And in 1866, Adrien Cordiglia photographed Remedio D’Avalos and His Hidden Nurse, Mexico August 15, 1866. A picture in which you can see the Black nurse hiding behind the curtain while holding up her white master’s baby. With these example in mind, the Mother show in Bonn was actually less diverse. Nevertheless, both shows addressed trans or queer experiences: In Bonn it’s the drawings of Paloma Varga Weisz and in Düsseldorf it’s Sumi Anjuman’s (Millennial, Bangladeshi) photograph I Am the Mother Too (2019).

Kunstpalast featured plenty of traditional representations and many works criticizing traditional representations. They also critically interrogated representations of motherhood during the Nazi dictatorship. But only a few works offered alternative, utopian representations. In Bonn, Margot Pilz’s The Last Supper (1979) suggests a Matriarchal utopia, a concept I was missing at Kunstpalast. Neither do I remember any discourse on representations of “Mother Nature” except for an allusion in the label for Max Ernst’s Mother and Child in the Forest by Night (1953).

And now what?

Speaking of motherhood is always a dilemma. If you focus on motherhood, you suggest that carework is a woman’s domain. If you include fathers or broaden the topic to parenthood in general, you might erase motherhood as the exploited base of society’s infrastructure.

In the Kunstpalast room Family Configurations, the final sentence of the wall label was “Art reflects a shift from the question of ‘Who is the mother?’ to ‘Who acts as a mother?’”, Or rather, “who acts motherly?” as a more correct translation of the German “mütterlich”. And that really left a bad taste in my mouth because the description “motherly” still implies certain values and judgments of how mothers are supposed to be. We’re still stuck in the circle of affirming gender expectations rather than deconstructing them.

One question in the very end of the show is “What can motherhood mean in the future?” and yet, the show suggests no futuristic visions, no Donna Haraway A Cyborg Manifesto in sight. That would have been a great keyword for AT LEAST Louisa Clement’s Attachment disorder (2021), a photograph of a robot mom holding a human child which was featured in Bonn.

Kunstpalast concludes with an okayish participatory space where visitors can doodle their thoughts on the backside of the seating area. I’m not a fan of this approach because it gives visitors a fake sense of participation: You burst out your pent-up thoughts and emotions onto the wall and get a sense of relief while the institution can barely do anything with the layered doodles; it’s not useful for further work. But I do appreciate the leaflets with help lines connected to motherhood.

And yet, MAMA offers just enough subversion to let a progressive audience (perhaps) give it a chance, but remains conservative enough to not alienate the traditional demographic. Mother, on the other hand, is not afraid of alienation. It doesn’t owe you a good time. And neither does it need to present an outlined narrative.

MAMA: From Mary to Merkel, until August 3, 2025, at Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf.

MOTHER, until April 25, 2025, at Galerie Gisela Clement, Bonn.

Kunstpalast

Ehrenhof 4-5

40479 Düsseldorf

Galerie Gisela Clement

Lotharstrasse 104

53115 Bonn

Tomorrow, I’m leaving for Venice again! Can’t wait to share what’s going on in my second city. And until then…

See you soon!!!

Jennifer

The Gen Z Art Critic

In an earlier version, I stated that Felicity Korn was the curator of the exhibition.

I saw the Mama show in the Kunstpalace, I left with an overall feeling of disappointment. A conservative mainstream approach giving nothing new. I look forward to seeing “ Good Mom/ Bad Mom” @centraalmuseum and am hoping it gives a more rounded version of motherhood/

mothering.