Monumental Nudes: Harold Stevenson in Venice

Milanese Gallery Tommaso Calabro opened their new space in Venice with a show on Harold Stevenson (1929-2018, American), honoring his love for the lagoon and tender visions of homoerotic intimacy.

Usually, I write about recent, contemporary art. But when I saw Harold’s paintings from between the late 1950s and 1970s, I was convinced they could’ve been fresh out the studio.

With love from Venice

Harold was deeply connected to Venice. He exhibited here in the 1960’s twice during the Venice Biennale in shows organized by gallerist Iris Clert (1917-86, French-Greek). In 1968, he also collaborated with Murano glass maker Gino Cenedese (1907-73, Italian) on glass sculptures that are included in this show. I loved the wall text for these: Back in his native Idabel, Oklahoma, Harold recalled the way he'd always discover new details on his commute between Venice and Murano and how Gino and him were finding ways to preserve the heat, the liveliness of the hot molten glass in its final cooled down form. In those lines, I feel the love and appreciation the artist had for Venice.

The glass pieces presented in the show refer to the lagoon. There’s a baloony version of the iconic hat of the Doge – the historical ruler of Venice –, the city’s famous campanile tower (which looks like a cake I want to take a bite of so bad), and Unicorn of the Sea (1968) in the form of a monumental canna, a glass blowing pipe held at the base by two fingers.

Pointing out what matters

Fingers appear all over Harold’s work, even beyond his Lunar memories (1968) pieces in the form of tinted blown digits encapsulated in glass orbs. They show up in his paintings caressing, pinching, and stroking.

In Western Art History, fingers and hand gestures played important roles in storytelling. Hands crossed over the chest conveyed devotion or agony. Pointed fingers guided the eye to what’s important in the picture, what really matters. I think of Raphael’s School of Athens (1509-11) centering the ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle: While Aristotle points to the sky, referring to the spirituality of philosophy, Plato holds his hand above the ground, hinting at a more pragmatic approach to knowledge (down to earth even, if you will).

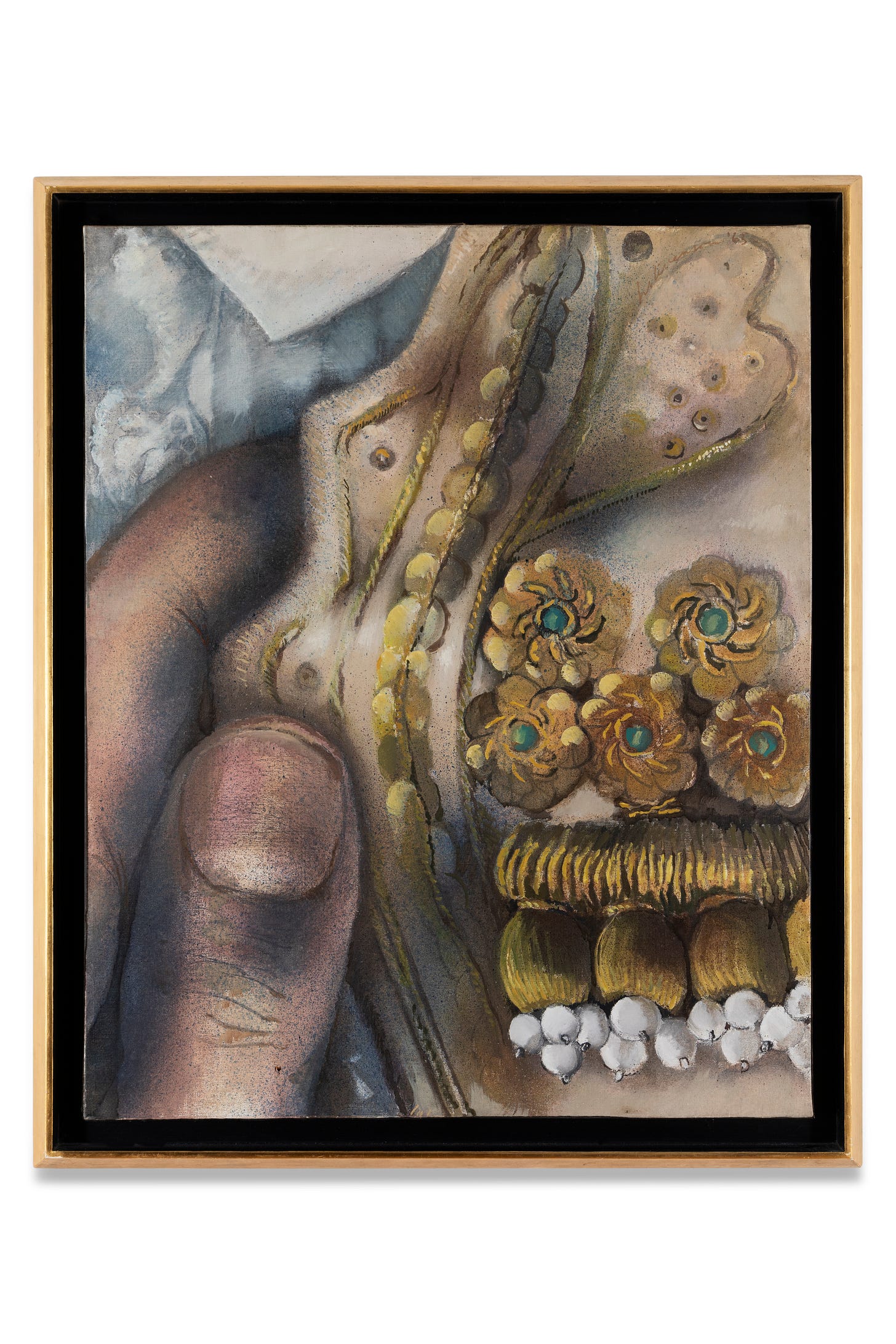

Harold combines the sensuality of fingers and allusions to Italian art history in a painting from 1970: Set against a gold-leaf background like those of Medieval devotional icons, two large digits caress a dark male head that turns both sculptural and phallic under their touch. This interplay between human flesh and gilded monuments is present in many of his paintings.

In an untitled work from 1964, Harold covers the groin of the painted male nude with a fig leaf, silvery as if broken off a statue. And in yet another work from 1971, the male head of a sculpture is set against the rosy skin of a nude. These close ups of naked bodies remind me of his contemporary Joan Semmel (Silent Generation, American), who in the very same period turned naked bodies into fleshy landscapes as in her painting Secret Spaces (1976).

Where Harold shyly covers a groin with a fist, he then goes on to turn an erect penis between spead legs into a monumental column, albeit a deteriorated one. Quoting antiquity makes sense in depicting homoeroticism, given that sexual relationships between men were widespread in ancient Rome and Greece, where it was sometimes even part of philosophical mentorship.

The Altar of Peace

In 1972, Harold created one of his most famous paintings. A colossal piece measuring 2,5 x 6,5 meters and filled with human and sculpted bodies mingled in sex. The Altar of Peace. The composition is neatly divided into three parts through a rectangular column and the twisted body of a man wearing a winged helmet, the symbol of the Greek messenger God Hermes. One central figure lies on ornamental brocade fabric I thought of as Venetian. With its spread legs, it reminded me of Gustave Courbet’s (1819-77, French) L’origine du monde [The origin of the world] (1866)

I was surprised to learn that this piece criticises the Vietnam War in it’s brutality and pointlessness. Surprised, because I first didn’t see violence in it. The reclining man on the lower left receives oral sex, I interpreted his expression as ecstasy. A female head closer to the center seems motionless, I might have even seen a smile on it. Otherwise, most faces are hidden behind limbs or pieces of sculptures. In the upper right corner, one figure buries their head as if in desperation, changing the initial interpretation as an orgy to one of assault. Now that I think about it, the ruins all around allude to distruction, and distruction goes hand in hand with violence.

I struggle to understand why the artist chose to set this scene in antiquity. The text from the original 1973 show catalogue argues that it's “set in a pagan mode, as if the horrors of contemporary war were too great to be encompassed in a contemporary context”1. That’s odd. To get empathy for non-white lives, Harold had to set the violence historically and geographically in a different context? One that was in his time still assumed as white? I mean, ancient Greece was long considered the origin of white culture as a justification of White Supremacy…

Approaching paint and the past

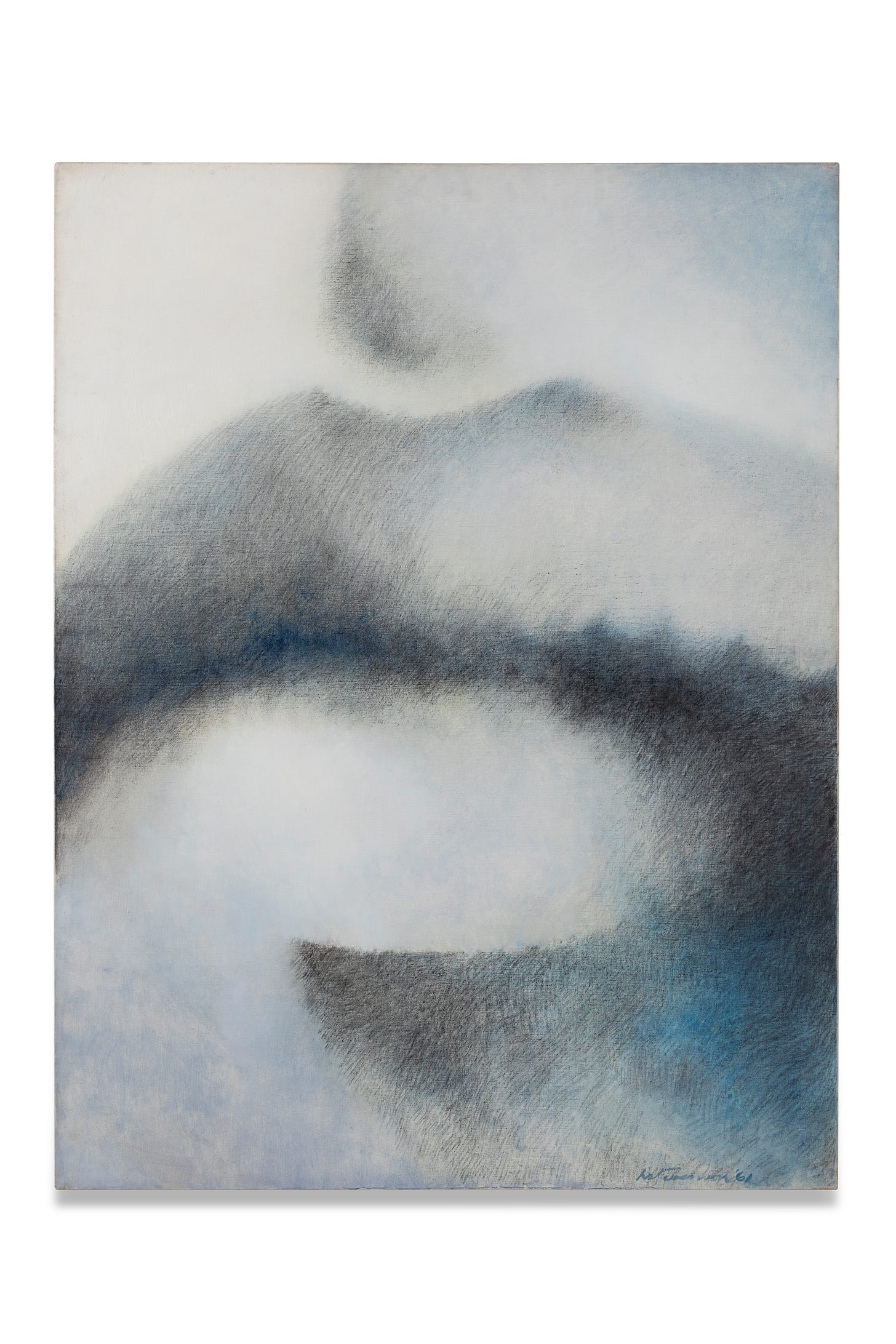

Looking closely, I noticed Harold’s not simply applying oil paint with a brush. He creates depth through sprinkling and cross-hatching paint, which is originally a drawing technique. I was reminded of a young artist using a similar approach for similarly homoerotic paintings, Louis Fratino (Millennial, American), who is coincidentally exhibiting nearby at the current Venice Biennale.

Harold’s greyish close ups of sculptural faces turn hazy. Not imposing like the original monuments but tender and gentle, slowly but surely dissolving into abstraction. His look into the past turns nostalgic. Not in a way that dangerously glorifies “the good old times” but that asserts and celebrates the existence of male intimacy that was falsely denied by historians for centuries.

Harold Stevenson is on view at Tommaso Calabro through July 27, 2024.

Tommaso Calabro

Palzzo Donà Brusa

Campo San Polo

2177 Venice

Website

IG: @tommasocalabrogallery

Congrats on the new gallery space! What do you think of Harold? If you enjoyed reading his work, please let me know in the comments and like this post. Also, don’t forget to share with a friend! Btw, please consider subscribing for a payment plan to support my writing.

See you soon!!!

Jennifer

The Gen Z Art Critic

Dotson Rader: Extracts from Harold Stevenson, Altar of Piece, exhibition catalogue, Alexander Iolas Gallery, New York, 1973