The Proof of Innocence: Reza Aramesh in Venice

An artist creates monuments for modern-day martyrs. Is this way of remembering political violence appropriate? And how might idealization be problematic?

In Anonymous Remembrance

In recent years, activists have toppled monuments all over the world. Monuments standing for oppression, subjugation, and violence. All personified in a figure. Opponents to these protests argued – and still do – that the statue can’t be condemned for the crimes committed by the actual person. They say stone is innocent, declaring the monument itself a new victim. A martyr. Questionable, to say the least.

The Chiesa di San Fantin is a Renaissance church turned exhibition space in the heart of Venice where historically, the Order of San Fantin took care of the condemned in their final days before execution. Reza Aramesh (Gen X, Iranian-British) builds new monuments for contemporary saints in this very same building. Made of marble, they are dedicated to non-white victims tortured and murdered in conflicts around the globe which, as curator Serubiri Moses (Millennial, Ugandan) specifies in the catalog, the Western world fueled to gain capital. Unlike Catholic saints with their detailed biographies and unique cults, Reza’s are anonymous with their identity limited to a bureaucratic record (we’ll get to that).

The Material of Memory

In the past, Reza often worked with archival war report photographs, performances, and polychrome sculptures. These latter sculptures were widespread in the Middle Ages. Made of painted wood, these figures of saints aspired to be life-like, imitating skin, fabric, and even tears. Reza’s use of a medieval technique was already a good fit to depict political prisoners. They have something important in common with saints: Suffering and death for their beliefs.

In this show, Reza focuses exclusively on white marble. But is marble an innocent material? A material embodying imperial Greek and Roman ideals – including the historically corrected idea of whiteness –, later Catholic Counter-Reformational spirituality, democracy in Classicism post-French Revolution, and finally even fascist ideology? Notice how every phase goes back to Antiquity in one way or another. Is a Western mode of commemoration appropriate for empathy with victims of same Western violence? The suggestion of (ethnical) purity can’t be washed off a material that played with it for hundreds of years.

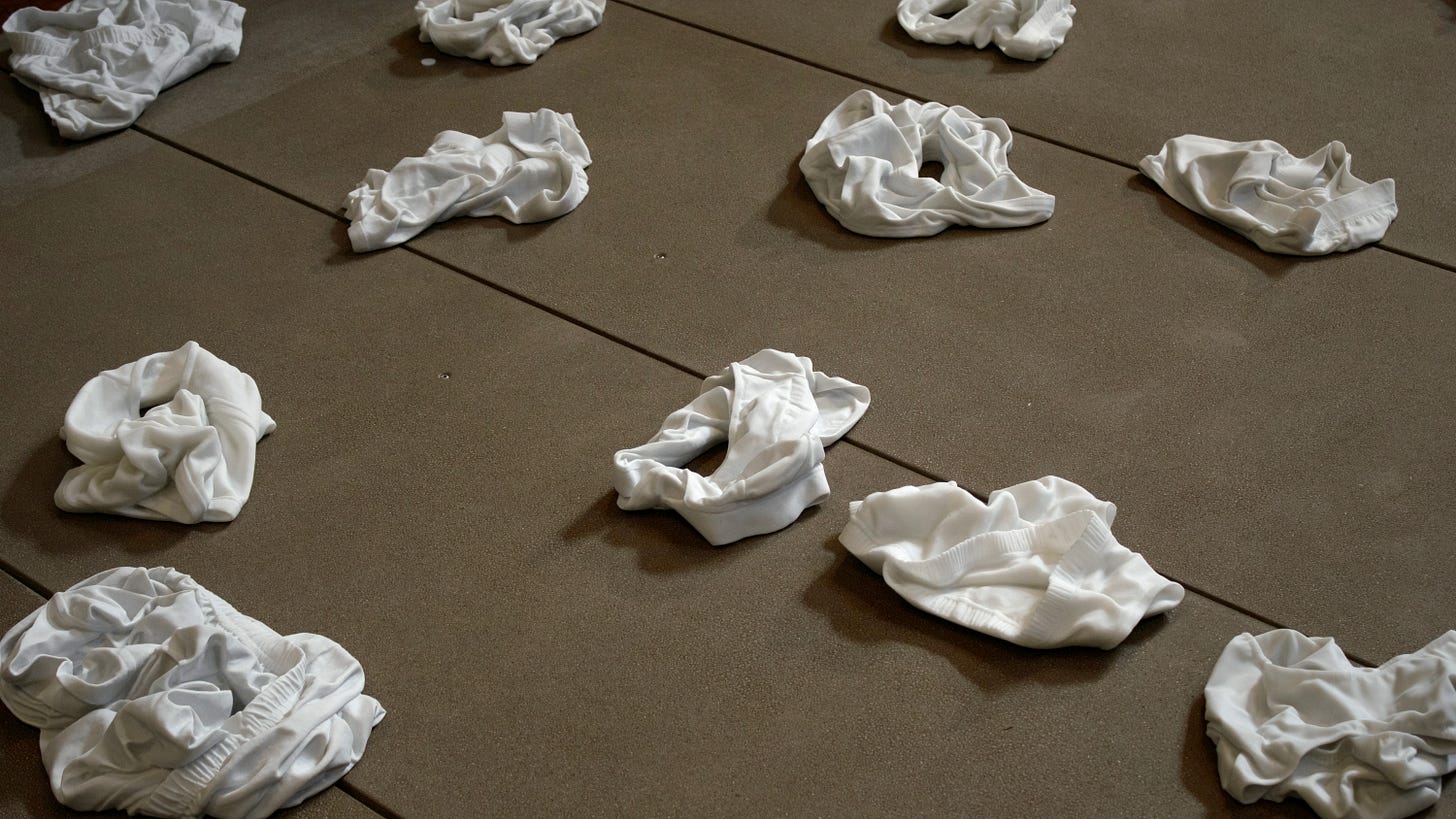

The church nave is lined with 207 pairs of marble boxers. Who left that underwear? Are those the remains of the apocalyptic rapture of the saints? Those are what’s left of detainees, or rather what detainees are left without. Stripping away all dignity, the imprisoned are undressed to full nudity, the humiliation ritual made part of the torture.

A Funerary Song

Instead of liturgical chants, solemn male voices expand in echoes throughout the space. It feels weird to call it an exhibition. The spiritual energy of the space doesn’t let me. Each voice recounts one of 207 so-called “actions”, the silence in between as grave as the meaning behind each number. Every action includes the name of the prison and the day the action occurred between the 1950’s and 2023. Each action stands for the torture and murder of an imprisoned individual. What exactly happened on those days is concealed, blacked out, classified, censored.

Three larger-than-life sculptures tower over the once sacred space, one for each side aisle and one positioned in the chancel. They almost glow against the darkness of the former temple. In various stages of dress and undress, they are stripped naked just the way Jesus was before getting nailed to the cross. A parallel evoking not only suffering but saintly qualities as well.

Turning the Spiritual Sensual

Beyond the saintly, Reza uses seduction. The sculpture Site of the Fall – Study of the Renaissance Garden, Action 245: At 4:00 pm, Friday 08 September 1950 (I know, that’s a long title) stands elevated on a pedestal. A young man raises his head towards the ceiling, a T-shirt covering his head and eyes, his pants dropped to his feet. The timeless perfection of this body is disturbed by his sneakers and boxers. With his hands tied behind the back, this young man resembles a both vulnerable and sensual Saint Sebastian anticipating the arrows that will in an instance pierce his flawlessly sculpted body. The soft marble fabric restricting him seems to subtly play with BDSM.

Sexuality is a red thread in Reza’s work, as he already worked with queer art history by recreating Félix González Torres’s (1957-96, Cuban-American) Untitled (Go Go Dancing Platform) (1991) for the Havanna Biennial 2022 and exhibited in queer bars and clubs in Williamsburg back in 2013 as part of his multivenue exhibition 12 Midnight. And just like the artists of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Reza doesn’t make these martyrs suffer, but lets them dwell in ecstasy instead. Physical pain becomes spiritual pleasure.

Site of the Fall – Study of the Renaissance Garden Action 498: 9:30 am, Wednesday 09 December 1953 portrays a man standing with his feet hip-width apart, fully frontal, arms dropped to the side as his pants slightly slide off the hips. The attention to the body is astounding. A slight mark of the marble turns into a scar on his stomach, even though these bodies appear otherwise smooth and polished. Not a trace of violence is imprinted on the skin. Reza doesn’t purely restore the dignity of these victims. He eroticizes them, allowing viewers to feast on their beauty. But isn’t this sexualization dehumanizing in a way?

Where’s the Redemption?

Reza switches the active parties in the infliction of pain. The sculpted prisoner of Site of the Fall – Study of the Renaissance Garden Action 218: At 8:26 pm, Thursday 16 November 2017 is undressing himself, lifting his shirt instead of being undressed by his offenders. An interesting choice. To fully leave out the perpetrators. A questionable one, maybe. It puts these actions into the passive voice, as the detainees are undressed, tortured, and killed by some invisible force. Reza increases the distance between the victims and aggressors, turning their fates into inevitable tragedies rather than preventable crimes.

His sober, line-encompassing titles contradict the sensual figures they are assigned to. These cold descriptions seem to be written from the perspective of the offender: A human being turns into a number, a series of signs, a bureaucratic lifeless entity. Yet, if the victims were only seen as objects, how do you explain the passionate violence? The immensely cruel modes of torture used precisely to crush the assumed dignity of each victim?

Head studies rest on the steps in front of side altars as if beheaded offerings to the Gods. Chiseled T-shirt fabric and underwear tightly wrap around them. Some mouths are slightly opened as if in ecstasy, just like Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s (1598-1680, Italian) Saint Theresa (1647–1652) when the angel pierced her heart. There they lie, facing upwards, awaiting the redemption promised by the biblical scenes behind them.

Growing up, I always wondered if the brutal fates of saints were told as threats or encouragement. Now I think of the condemned of San Fantin: Was death their sentence or salvation?

Do you want to bring an offering to modern saints? You can do so at Reza Aramesh: Number 207 until October 2, 2024, at Chiesa di San Fantin, Venice.

Chiesa di San Fantin

San Marco 320/A

30124 Venezia

Website

Instagram: @number207art @rezaarameshstudio

If you are in Venice, make sure to pass by. This show surely impressed me. If you liked this review, consider subscribing. As a free or paid subscriber, you can support my work and help me make art criticism more accesible. You can also like my posts and comment as a subscriber. If you know someone who might be into this one, hit the share button!

See you soon!!!

Jennifer

The Gen Z Art Critic