Firing Chekhov's Gun: Henry Taylor at the Whitney

Henry's (Baby Boomer, American) first NYC show took me on a journey through a family photo album, a hall of fame, the intimate whispers of a mental hospital, and nightmares unfolding under daylight.

Painting people, painting life

Henry makes portraits. Portraying someone or something means balancing the idea of how it is and how you know or feel to know it. Both sides meet somewhere in the middle of a portrait. Henry grew up in LA and painted the people he knew and met on the street. Sometimes they are aware of him, annoyed by his presence as if interrupted. Sometimes they are fully absorbed in what they do. He often chooses tight taller-than-life vertical formats and views from below, placing the viewer underneath something monumental.

These chunkily painted portraits are the result of memories, snapshots, in-person sittings, and newspaper clippings. Frozen and vivid images, preserved pictures and moving moments create an image of what a person is like and how Henry feels to know them. Too Sweet (2016) is a young man framed by the bright LA sky holding a piece of cardboard and throwing up a shaka as if just greeting the passerby. Gettin it Done (2016) might be the fed-up attitude of the young man rolling his eyes as he is growing tired of the long process of getting his hair braided.

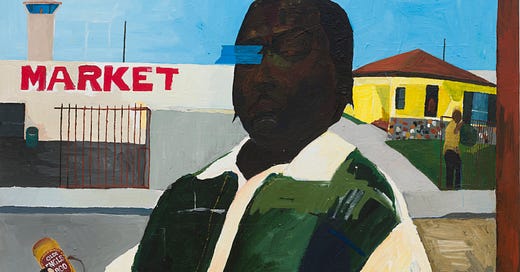

Sometimes, Henry highlights his subjects’ attentive eyes in sharp contrast. In other paintings, they diffuse in the skin, giving no chance to look into them. Fatty (2006) wears an emerald green and white bowling shirt and suspiciously raises an eyebrow as if interrupted by something outside the frame from sipping the Olde English 800 malt liquor in his hand. It was the flying rose in the left corner that caught my attention. But as I kept looking, I realized that the person is standing on a threshold, marking the change from the brown pavement of the suburbs on the right to the grey asphalt in front of the prison market on the left. It takes only one wrong step. One second of inattention. There’s someone in the front yard of that yellow house standing behind just the same grid as that of the prison. I notice a piece of blue tape on the protagonist’s right eye. The very same blue of the prison surveillance tower in the distance. It’s all taped.

A series of graphite drawings on paper stands out. 19 drawings in the show are from Henry’s time as a psychiatric technician at Camarillo Mental State Hospital in California. During the night shift, he drew thin outlines of patients, sketching a person he can only get to know partly and never as the full picture.

Legends

Henry portrayed a lot of celebrities, curators, athletes, politicians, and entertainers: Tyler the Creator on a suitcase, Jay Z full frontal, Barack and Michelle Obama casually on a sofa. The snapshots from magazines and newspapers that become part of these portraits lack the story and their whole environment. Henry inserts these cropped images back into a painted world where they get to have meaning again. The image of Martin Luther King Jr. in Untitled (2016–22) stretching out his hand could be taken from a photograph you would see in a newspaper. He’s now in a park playing football with four boys, gazing out at the viewer. Is the white car on the right parked or slowly driving by? What are the three white men in black suits waiting for?

Gallery 6 of the show features the large-scale installation Untitled (2022). A group of mannequins wearing the iconic leather jackets of the Black Panther Party is facing forward. There’s a Black Panther banner on the wall behind. Randy, Henry’s brother, was active in the party’s California branch. The California State Flag and the US flag frame the group. I notice a slit: a picture of strict eyes surveils the room. To the left, Henry hung black and white photographs of 15 recent victims of racialized violence. History is now.

Simply trying to move on

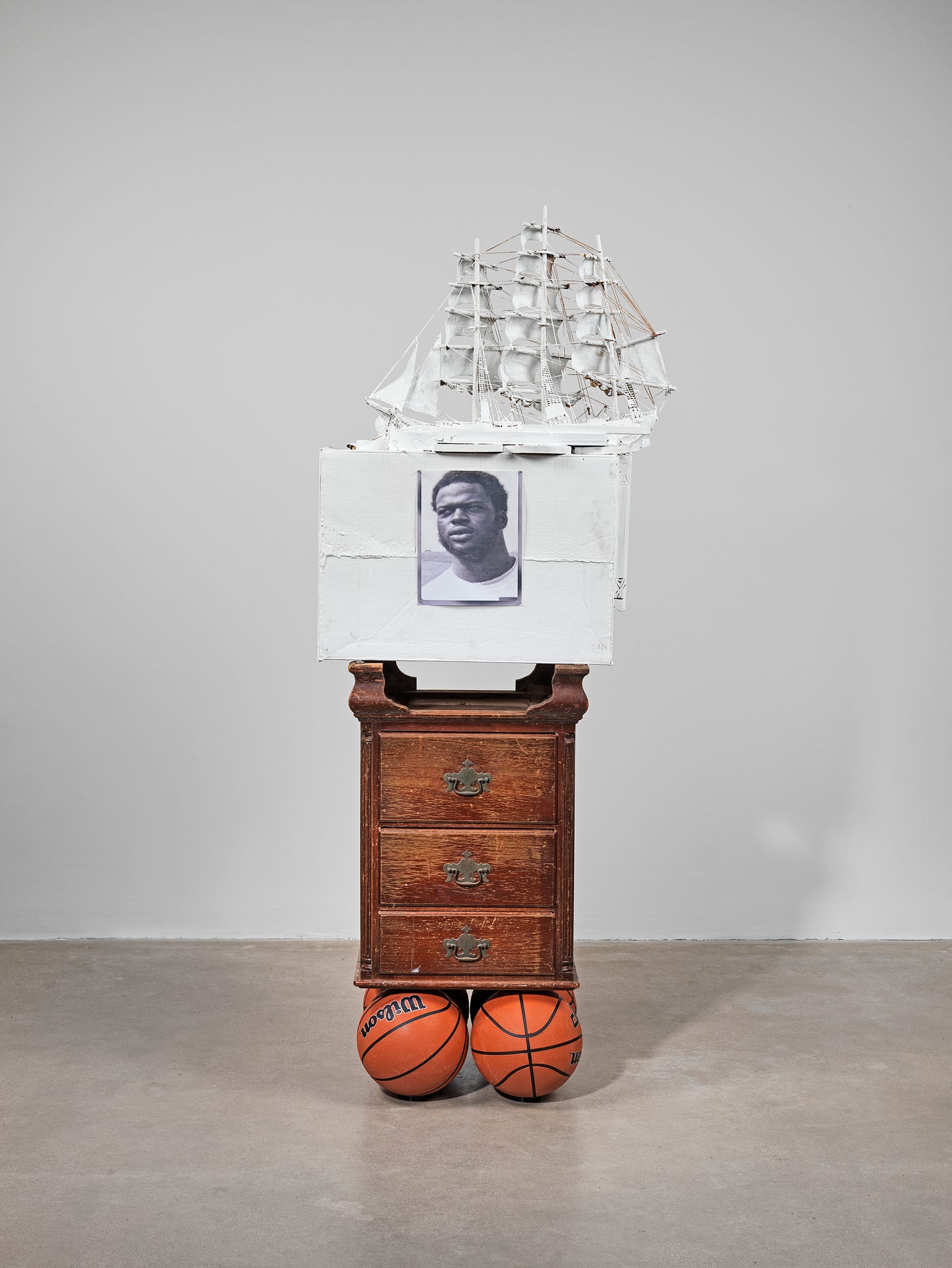

Henry doesn’t paint brutality or horror. He paints life. And fear is just part of the life he knows and the people he paints know. The painful memory is in the Girl with Toy Rifle (2015) getting her back-to-school picture taken by a proud parent. Smiling, she’s standing on the porch like a Confederate soldier on top of a monument. What will they see first? It’s there in the form of trauma and an involuntary flinch of the letter K aligning in three Kellogg’s cereal boxes of Untitled (1990s). American Pop artists like Andy Warhol (1928-1987) and Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) used cheap everyday objects to make fun of a consumption-driven culture. Henry’s so-called “painted objects” use a Fred Wilson (Baby Boomer, American) approach to point out the consumption of Blackness.

I am, too, inside the car in THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH! (2017), looking at a man lying in his seat and looking up as an anonymous white body threatens to use a gun. I can’t even tell whether it’s a cop. What difference would it make? Henry paints my position in the painting inside this car, but I am not. In reality, I am observing from a safe distance. Just like in the large panoramic scene Warning shots not required (2011), I get to sit behind the glass with a front-row view on the chaos unfolding outside.

Waves of ease and unease carry through the show. I realized that the curators use a theatrical technique: Chekhov’s gun. This plot device named after the Russian writer Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) follows a very simple rule: If there’s a gun hanging on a wall in the first act, the gun will be used in the last act. The subtle tension created in Henry’s portraits eventually escalates. Nobody might die on canvas, but someone might a few streets from Henry’s studio. The guy in THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH! (2017) might survive that confrontation in the painting (Diamond Reynolds watched her boyfriend Philando Castile getting shot by the police that moment), but somebody else won’t in the world out there. Death is not only hiding in the dark. It’s walking you through this show. But this is not a theater. The actors will not rise and take in the applause of the fooled and mesmerized audience. The shot is always real.

You can get a look at painted LA with Henry Taylor: B Side, until January 28, 2024, at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Whitney Museum of American Art

99 Gansevoort Street

NY 10014

Website

I hope you enjoyed walking with me through this exhibition. Adding another Tyler the Creator song to your playlist? Let me know your thoughts, leave me a comment, a like, and if you’re down, I’d appreciate you sharing this post with a friend. Thank you for being here.

See you soon!!!

Jennifer

The Gen Z Art Critic