Déjà Vu Diaries: Cécile Lempert at BRAUNSFELDER

Cécile (Millennial, German) brings personal and foreign memories onto canvas, pulling in with gentle nostalgia.

Lives centuries apart

A lot of beige. Quite a lot soft brown. Haziness. I feel like I’m looking at something through dust particles levitating in a beam of light. Those are the sensations that Cécile’s art gives me.

For the paintings presented at Braunsfelder, she browsed family archives. Specifically, the photographic archives of the Dildilian family. As Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire, many members of the family worked as photographers, documenting the life of the Armenian diaspora from 1888 to 1930.

Cécile chooses moments of calm. In Im Badezimmer [In the Bathroom] (2024) two boys sit in a bathtub, one is scratching his forehead, the other looks down, lost in thoughts. Cutting Mint II (2024) shows two girls working in the garden, carefully concentrating on their task. I feel the warm sunlight on the boy’s cheeks Ismael (2024) as he tiredly rests his head on his right arm. Photographs turn into drawings turn into paintings. And sometimes, they don’t even look like paintings. Hisous Dzenav 1916 (2024) looks like an ancient wall fresco that is slowly erased by environmental wear and tear. The inserted title fades like graffiti that couldn’t get fully washed off after several attempts.

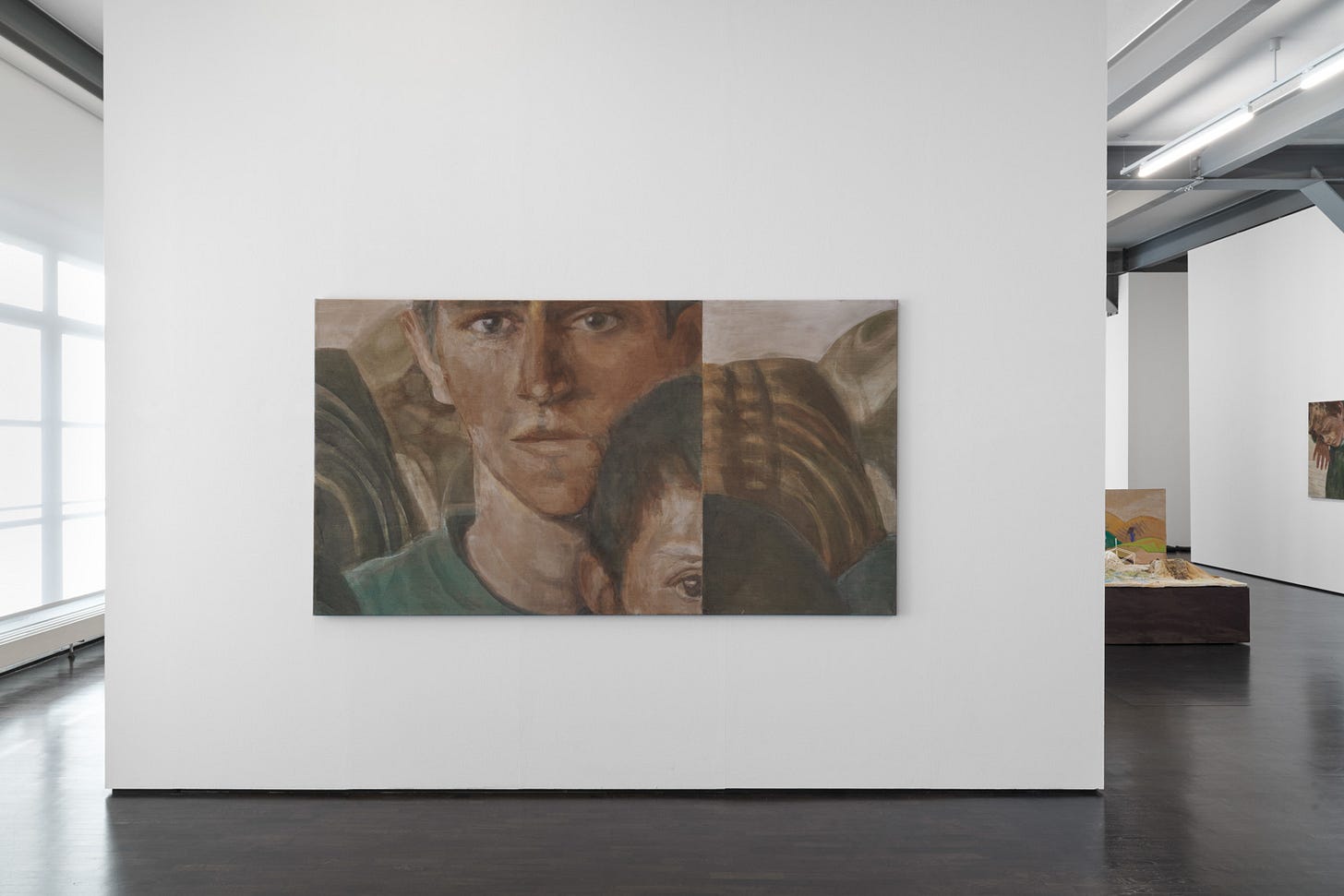

I feel like Cécile’s works have a lot in common with film. Her choice of earthy tones evoques the grainy texture of a yellowed out analog film. Two faces share a long horizontal canvas, a slit almost, for an untitled painting from 2024. Separated by a vertical line, they both look at something beyond the confines of the artwork itself. A moment of suspense. They appear frozen like an analog film that was abruptly stopped and two stripes got stuck together. As if doubling the image on canvas separates what image is one’s own and what is borrowed, the memory and what happened.

A sense of closeness

I love the way Cécile uses raw unprimed canvas. Its natural sepia tone adds even more nostalgia to the historical pictures. Cécile goes for measurements similar to close-up shots. These fragments convey intimacy and familiarity beyond physically standing close to the people depicted.

Take for example Spiegelung [Reflection] (2024). I am so close to the scene, I’m already breathing into the boy’s neck who has turned away from me to face the girl to the right. She’s carefully examining something in her hand, something cut off from my vision. They seem blithy unaware of somebody looking at them.

These images being distant memories rather than something happening before my eyes is beautifully translated through technique. Cécile uses distemper and pastel on canvas. Distemper is a very fragile type of paint that was used for centuries by artists in Europe and East Asia. Dried, it looks very different from its wet state in the process. And, sadly, it dissolves fast and is easily lost to time. Isn’t this the bittersweet fate of memories?

The texture of the canvases brings back my own memories of heavy linen and dust illuminated by the glaring hot sunlight entering a window on a late summer afternoon. These works make me homesick, they make me miss my childhood summers.

Devotion to details

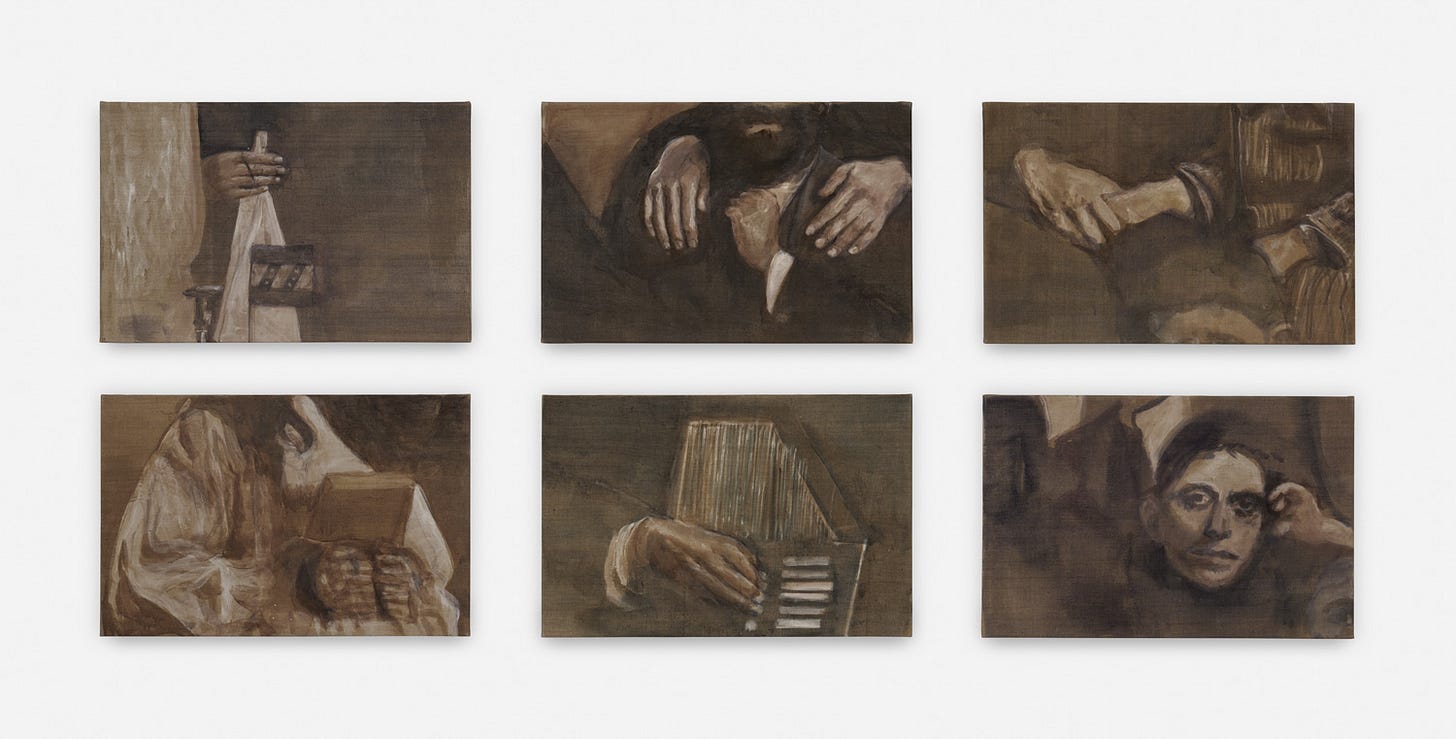

Cécile has an affinity for hands. Ironically, Holding Hands (2024) doesn’t show two people embraced in touch but rather seperate sequences side by side. The delicate attention to soft texture reminds me of the artists of the Cluj School. Especially Szabolcs Veres (Millenial, Romanian) comes to mind. Hands are also central to her 6-part work Apostolic, 6 January 1916 (2024). Hands rest on shoulders, they clutch a white piece of fabric, they play an accordion, they rest in a lap, they clutch a book, they prop up a head. I think of the hand gestures of saints in Christian iconography. Cécile takes up the imagery of Armenian frescoes and miniatures in watercolors. Just like in the paintings, the figures here are often separated through both vertical and horizontal lines cutting through, interrupting, tearing apart.

Slouching through the halls filled with these poetic paintings, I was a bit taken aback by a large cardboard landscape model. It was so different from Cécile’s other work that I initially doubted it was even hers. Drawings and papiermaché buldges imitate riverbeds and mountain ranges. The messiness is so unlike the tender attention to detail in her other works.

The playing around with archival photographs reminds me of Claire Tabouret (Millenial, French). While Claire enhances the uncanny and darkness of her chosen image through painting, Cécile brings a certain lightness into it. Not in the sense of banality, but rather gentleness. Like the feeling of relief when you can release tension around those you know well.

Memories of people living a century ago are overlaid with those of the artist alive today. I couldn’t find anything on whether Cécile has any Armenian ties. Because if she doesn’t, what prompted her to choose this specific legacy? Is mashing those foreign memories with one’s own intrusive or empathetic? What happens if you pull a deeply personal memory out of a family album and give it a new space to unfold? It becomes a stranger in an environment it wasn’t made for. And at the same time, the memory comes back to life as it connects with the people who see it now. But as Earl Nightingale said: “The time will pass anyways”.

Go back in time with Cécile Lempert: Who makes the solid tree trunks sound again, through May 18, 2024 at Braunsfelder.

BRAUNSFELDER

Geisselstrasse 84 - 86

50823 Cologne

Website

Instagram: @braunsfelder @cecile_lempert

April 24 was Armenian Genocide Rememberance Day. You can educate yourself on the history of the Armenian diaspora on the website of “The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute” Foundation. If you enjoyed this review, I’d really appreciate you leaving a like or a comment with your thoughts. And share this review with a friend, if you don’t mind…

See you soon!!!

Jennifer

The Gen Z Art Critic