#3 In the studio with Sarah Kürten

I met Sarah (Millennial, German) in her Cologne studio after seeing her artothek solo show a couple weeks earlier. We talked about fake lifestyles, womanhood in the arts, and finding the right words.

February 29, 2024. I only realized it was a leap day as I sat down to write this very first sentence. I rang the bell of the 1960’s two-story house. As Sarah opened the yellow glass door, I noticed the yellow tilework in the corridor. It reminded me of the rectangular transparent foils she used in the careful what you wish for exhibition. “It’s similar, but that’s just a coincidence,” she replied.

Sarah set up her studio in the house her grandpa built in 1962. “I’m fortunate to have this space, even though it’s not as cool as one of those industrial lofts”. I noticed the floor again: dark brown parquet flooring arranged in small diamond shapes. We switched to her flat next door to get some tea. I kept petting her dog Bombola as we talked.

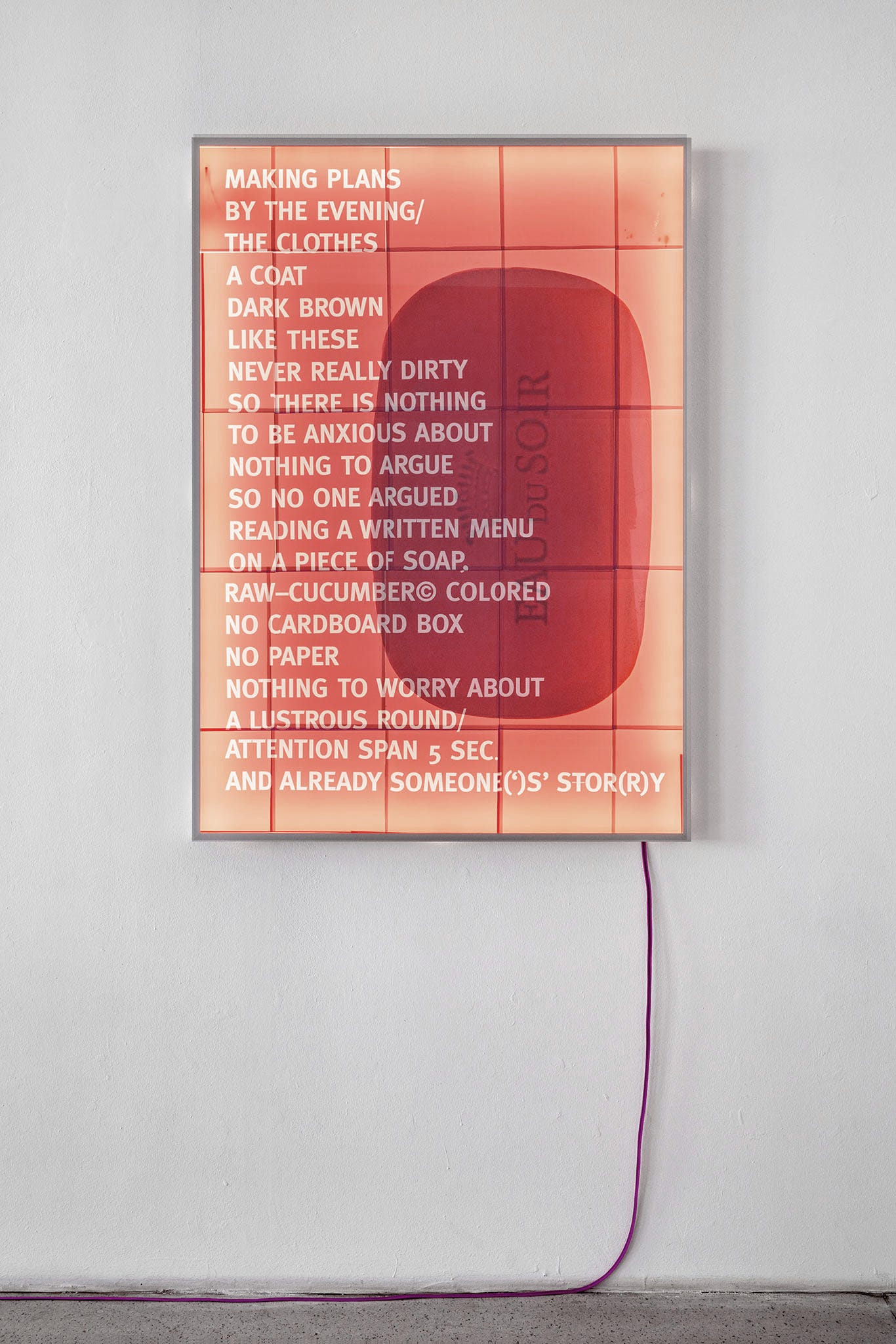

The moment I walked into her exhibition, I knew I had to meet her. In her art, Sarah expresses ambiguous desires and pulls back the curtain on lifestyles that look perfect on paper. Or Instagram. Poetry and vintage aesthetics mix with subtle references to here and now. Sarah mainly works with collages, lately displaying them in lightboxes that literally shed light on what nobody wants to expose about their picture-perfect, curated life.

Her collaging method follows countless meticulously executed steps. She uses both found footage and self-shot pics. Sarah arranges the pictures on her desk and takes a pic of the result with her phone, keeping the layers, shadows, waves, and irregularities of paper on the snapshot. She enlarges the whole image on her computer, rasterizing it. Then, she prints it all out and glues it together as a collage in two layers, one for the black-and-white images and one for the colors underneath.

I instantly connected to the way she describes the realities and delusions in the arts. The ambiguities of what success really is. The shame of not being part of the cool kids club that already made it. The stories she tells through her work not only connect to experiences in the arts but every area of life where the lines between wealth and poverty are simultaneously blurred and enforced.

The following conversation was edited for clarity.

JB How did you come up with the theme of careful what you wish for?

SK Back in 2021, I started working on class in art or the art world. I also shifted from human figures to objects as my motives. I was in Italy at that time. I live in the Italian countryside for part of the year, my life is totally different there. There are mostly farmers around me. I help with farming when I’m there, especially harvesting olives in the fall or doing other smaller things. During the pandemic, I gained a lot of distance from the life I had before and reflected on it. I was thinking about who art is really for.

I started collecting pictures on social media. They were supposed to be illustrations for a book. I concluded that social media is all about status symbols, isn’t that what it boils down to? You represent yourself all the time, you create an image to the outside world of how you would like to be seen. Many people I know who don't actually have such a high standard of living post how they eat oysters… Why?

JB Say less. My life in Cologne versus Venice? Worlds apart. How did you learn to work like that? With all those physical layers and stuff…

SK I came up with it myself.

JB For real? That's awesome.

SK But that took a lot of time. Some artists know right away what they want to do or at least have an idea of where they’re heading. That wasn't the case for me. I knew relatively early on that I wanted to make art, similar to how you knew with art history. Maybe I knew around eighth grade. I saw a [Alberto] Giacometti (1901-66, Swiss) exhibition and thought, that's the coolest thing I've ever seen, I want to do that too!

You suddenly develop a strange self-confidence when you know that you have to go down this path. But it took me a long time at the academy in Düsseldorf, I tried everything. I started with painting. Then I went to a sculpture class and tried all kinds of materials, and at some point, I stuck to minimal and conceptual art. And then I got into writing because I felt like everything I was doing was shit.

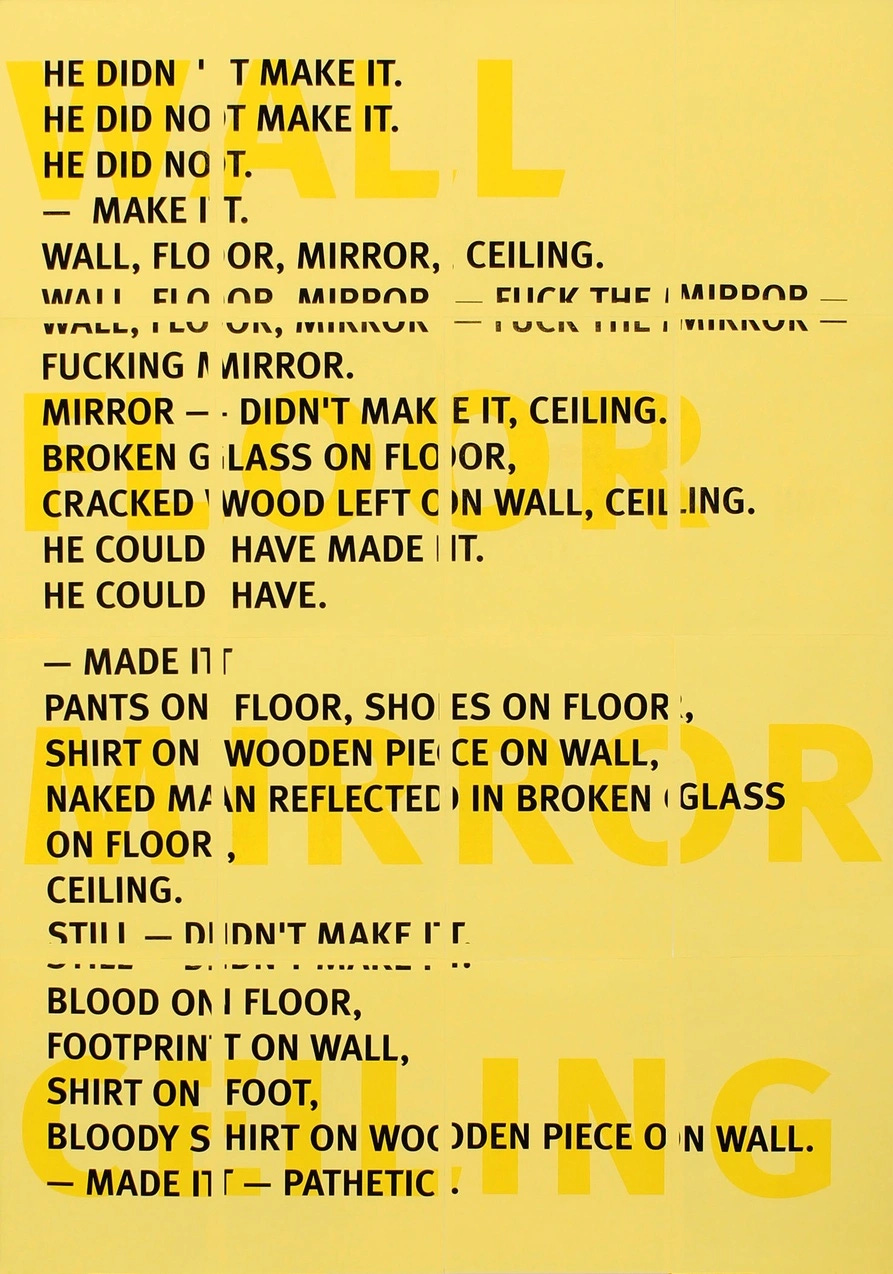

So I wrote about that frustration. That’s when these first self-reflective texts came about. Then I had this moment with my first work, which was called Wall, floor, mirror, ceiling (2015).

I finally had a breakthrough with writing. From then on, I worked text-based. I became interested in artists like Ferdinand Kriwet (1942-2018, German), Ed Ruscha (Silent Generation, American), or Lawrence Weiner (1942-2021, American), and I mean, there aren't that many who work with text or text only…

JB And there’s Jenny Holzer (Baby Boomber, American), too!

SK Right, exactly! She’s probably one of the most interesting artists to me. Eventually, I integrated pictures into my text works again. But that took a while.

JB Speaking of inspiration: The lightboxes in the show were giving Pop Art to me, is that a reference point for you?

SK Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008, American) is the most interesting of the pop artists for me. I like these enormous works that are practically like a huge wall piece…

JB Yeah I know what you mean, the Museum Ludwig has one with Kennedy on it.

SK Exactly. I think that's something I looked at a lot. And speaking of Pop Art, Claes Oldenburg (1929-2022, American) is very important to me, especially his writings. I find that era aesthetically pleasing, I definitely put myself into that category, no doubt. But there’s more that I look to for references.

JB I find the perspective in your work so touching. I saw your show with a friend and we had a long conversation about it. We felt seen in our struggling womanhood and it felt right in such a good, warm way. Especially as we both work in the arts and experience the precariousness of this lifestyle firsthand.

SK I know that all too well, I used to have a completely different life. I first came into contact with that high-end art world by assisting other artists while living in my 30-square-meter apartment and struggling to pay rent. You buy fast fashion and second-hand clothes which you hope might somehow pass for Maison Margiela at the next dinner.

Everybody wears black, of course, because nobody can classify that. And then you're so strangely worried about stuff like that. I don't think I've ever had social envy in that sense, but I did feel the frustration of never really belonging. Dinners are the most absurd part: You sit with all these people in restaurants that you could never afford by yourself. But you know all the social codes, so you don't stand out.

Artists make an effort to represent themselves to the outside world with a fake-it-till-you-make-it mentality. No matter what you say, secretly, you desperately want the fucking Celine bag so that everyone knows you’ve made it. Never before had I been in a society where these things mattered as much as they do in and around art.

JB May I ask about your upbringing? Class struggles become more visible once you mingle with those circles as an artist, but was class also an issue for you growing up?

SK My grandparents were working class. Then, my grandfather started his own business and built the house next door. That was middle-class logic. But everyone grew up in this late 19th-century house right here. Two families lived here with twelve kids or something. And I mean, this house isn’t that spacious. Class consciousness had a great significance for my parents in particular. I noticed how they repressed their origins and felt ashamed. They pretended that this past didn't exist.

Our family was doing quite well for a while, you could have considered us upper middle class. My parents were homeowners, we went on vacations and stayed in hotels, so I know all that. Our financial situation changed drastically just as I enrolled at the art academy, and my parents suddenly didn’t have the means to support me. I learned what it’s like to have no money at all. I had to financially support myself while most people who studied with me were supported by their parents.

JB Really?

SK Yes. In that sense, my history shaped me a lot because I've been through practically everything. And I mean, who can afford to study art like that? That's simply a factor if you come from a working-class household. Studying costs money in Germany, money you aren’t earning while attending university. You need money if you’re moving away from your family. And making art is expensive. You don’t get materials and workspace for free. If you’re not socialized in an environment that values art, you might not even know that being an artist is something you can aspire to. I think it's important to face this reality. But there are always exceptions. [Andy] Warhol (1928-87, American), for example, was a working-class kid.

JB True.

SK Beyond financial questions, it was still quite difficult for a woman at the academy to be taken seriously. Fellow artists of my generation and I realized what had been happening back then only years later. The environment was predominantly masculine. When I started, there were mostly male professors. And this idea still prevailed that art was a male domain, somehow. This kind of environment influences you subconsciously. Today you'd think of it as offensive. But that just wasn't on your mind back then.

JB I can’t imagine how much of that you must have internalized...

SK That was quite normal. You just accepted it for yourself. In the beginning, people called my work very masculine and I took that as a compliment. I thought that “masculine” means strong and people therefore take it seriously. Now I would think of it as an insult because it really is one. But calling it “feminine” is equally offensive. I don’t want my work to be gendered at all.

JB We’re both German, we’re having this convo in German, but we still choose to work in English respectively. What does it mean to you to write in English?

SK First and foremost, mental freedom. It's a foreign language that I speak reasonably well while allowing myself to make mistakes. I use words very loosely, writing in a stream-of-consciousness. I write everything down and correct it later. I often use words the sound of which I like and then I look up their meaning. That's exciting because sometimes they have meanings that I didn't expect beforehand.

When I write, I read everything out loud several times so that it sounds exactly the way I want it to. Sometimes I set the rhythm with the line breaks, I want this sound to pop up in the reader's head. Generally, using language in art is exclusive. But with English, even if you don't understand everything, I think there's still a relatively broad audience that was socialized with it.

JB That makes sense. I think German is somehow more geographically fixed. And even though English isn't a native language everywhere, it’s kind of a neutral bubble. I recently saw a meme where someone tries to break up with you in English and it goes I can't take that seriously, English is the language of movies, the fuck...

SK I was socialized like that, I perceive English as the language of pop culture and song lyrics. It’s much more relaxed and easy-going for me.

JB And how do you come up with your titles?

SK My titles... My titles... I always choose my titles afterward and quickly. Honestly, that's the real fun part. I browse through a book, stop at random words that attract my attention, and browse again, just the way the Surrealists approached writing. It’s like a word collage. You feel like the universe is crystallizing these words out of the page, but of course, that’s not true, you’re already in the mental state to find the words you want.

JB …Do you know the cheese-of-truth guy?

SK No, I don’t think so…

JB He throws a piece of cheese on a newspaper or book page and reads the words in the holes. It’s hilarious, although I suspect he’s manipulating the outcome with prepared pages. But given that you collage the words more or less randomly, many titles make a lot of sense. Like THIS IS AN AUBERGE - NOT A HOTEL (or A STONEMASON WORKS STEADY EVEN ON THE WEEKENDS) (2023) for example.

SK I allow myself some humor. I never titled my works in the beginning. And then I came across Meuser (Baby Boomer, German). Without the titles, I wouldn’t be such a fan of his work. All his pieces become a thousand times more interesting because he picks these hilarious titles like Wenn es am Montag nicht besser wird, rufen Sie noch mal an [If it doesn't get better on Monday, call again] (2002).

JB Love that.

SK Such a great title for four painted steel plates. Suddenly, this work is something else and you look at it from another angle. It’s also a cynical commentary on minimalist sculpture. And without the title, it would just be “painted steel” on a wall. You can really open up a new level with an intriguing title. I want to open all the doors in my work. I want it to be welcoming. I like working with what feels familiar but also offers mental exercise while touching people emotionally. Maybe that’s why I work with advertising aesthetics so much, even if the comparison might sound a bit out of pocket.

Sarah’s new book against a shadowy tree line will be published in early 2025. A sneak peek with a selection of poems is available on neuefotogafie.com

Thank you so much Sarah for having me in your studio! Make sure to follow @sarahkuerten on Instagram. If you enjoyed our convo, feel free to share it with a friend! As a subscriber, you can leave likes and comments on my posts, so let me know your thoughts!

See you soon!!!

Jennifer

The Gen Z Art Critic