#1 In the studio with Daniel Spivakov

While still in Venice, I visited the Ukrainian Millennial artist in his studio on the island of Giudecca. We talked about Bob Dylan, condoms, fear of failure, punk culture, and internet slang.

August 1, 2023. It’s a cloudy, hot, and humid Tuesday afternoon. The Venetian sky is radiating its particular bright blue that I love. Daniel is normally based in Berlin, but right now he’s in Venice for his participation at the Chronorama Redux exhibition in the Pinault Collection. Daniel greets me in his studio, paint all over his arms and 60s music blasting from the radio. “Look at my modern AC system”, he says laughing, gesturing at a fan running at full speed framed by the wide open windows.

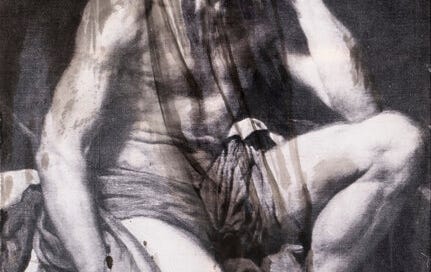

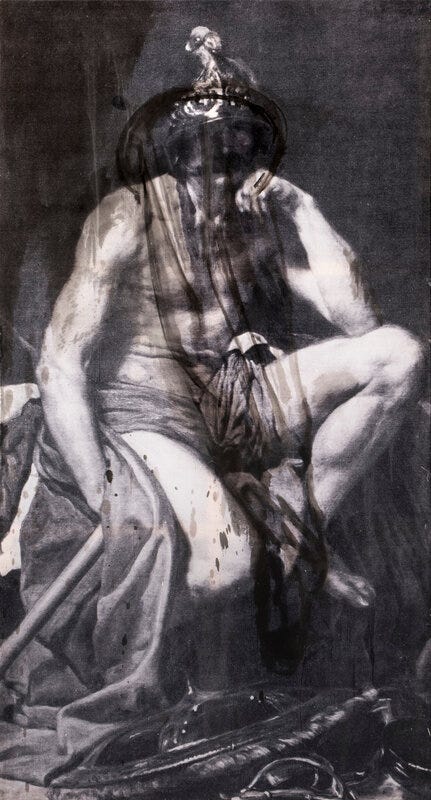

Daniel is currently working on a new painting series based on works by the Spanish Baroque painter Diego Velázquez (1599-1660). He starts with black and white photographs from a vintage book he bought back in Berlin. He scans the photographs and prints them on large polyester canvases which create a beautiful see-through effect you can’t get with normal linen canvas. Then, he paints them with oil. Daniel uses paint on the prints as commentary, highlighting what he is interested in. Some gestures turn into passionate, abstract outbursts of color, others into figurative forms like skulls and condoms.

Most paintings in this series are based on Diego’s religious paintings, one of them being a crucifixion. Art history has countless versions of Jesus Christ on the cross already, but Daniel keeps working with that image:

Well, we've seen each other's faces quite a bit too, you know? We've seen shoes quite a bit. We've seen grass, we've seen flowers. But maybe as an artist - I mean, I speak for myself - you're interested in new possibilities for the thing. And sometimes you're successful with that. Sometimes you're not. I think there's a level of banality to it. And so it's a challenge. Painting skulls is pretty banal, too. It's like an art 101 kind of decision, it's like, Okay, let's paint death. But sometimes you want to use these overdone things because you want to see if you can actually bring it to the point where it's going to be new again. You can find humor in things that are overdone. It's like a joke. It just has to work as long as people are laughing. Maybe it's similar to fart jokes. They're banal, you know what I mean? Maybe it has to do with human experience. And coming back to the crucifixion, it's the ultimate story of human suffering of the sacrifice of human godly nature.

One of those works, Mars, God of War (2023), started with a condom Daniel accidentally left in that vintage book once: He scanned the image with the dark stain on it and ran over the contours with black paint. Soon, he started draping condoms over saints. In The Supper at Emmaus (2023), it’s easy to mistake them for a veil (I sure did). An ejaculation of white paint becomes the ultimate expression of (un)holy ecstasy.

Well, these are just images. I mean, I paint a condom on top of Jesus. My personal beliefs I guess are irrelevant to the fact that I'm using Jesus because I could be using Buddha or something else. So I'm not trying to preach anything with the paintings. But I guess everything I do is related to my faith. So, somehow it's related, but painting the crucifixion is not, it's not more spiritual for me than painting a condom.

Daniel’s approach is the ideal example of Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935): For the longest time in art history, art was created for specific people, places, and purposes. Artworks were tied to their context. That changed with the improvement of printing techniques and most radically with the invention of photography in the 19th century. Suddenly, you can see the same image in a church, a kitchen, a museum, a book, a T-shirt, and a meme page. Now, images don’t have any context. They exist in thousands and millions of places and forms at the same time. Daniel’s art picks up that phenomenon: Painting is turned into photography is turned into physical objects is turned into scan is turned into print is turned into painting again.

It’s not the first time that Daniel used Old Master paintings as the foundation of his own art. In earlier works, he painted over Georg Baselitz (*1938, German) and Caravaggio (1571-1610, Italian) works. Daniel prefers working with oil paint instead of more modern acrylic. I was wondering whether it had to do with building on that respected artistic tradition:

Not really. Maybe. Somehow, maybe. But at the same time, it's just something that I like. I don't like acrylic. I don't know how to use acrylic. I use sometimes acrylic when I need it. But to me, it always stays too flat somehow. It's too plastic while oil has more possibilities for unexpected accidents or unexpected results. In these works you can see that you would never have stains like that, drips like that. Maybe it has to do with history. I'm trying to bend the material, you know? I paint thick. And then in a couple of hours, I keep looking at it and then I take a rag and smudge the whole thing and then I come back, look at it again. With acrylic, you do one move and that's it. You have to leave it. And that's it.

Daniel keeps the dark, gloomy contrast of the printed images. It makes them look like they were randomly discovered in a haunted mansion. Daniel uses a very limited color palette: Greyscale, a bit of white, some dark purple. The orange and pastel pink become even more surprising, like a firework you didn’t expect to unfold right in front of you as you walk through the night.

The following interview was edited for clarity.

JB Why do you choose large canvases? I think I've not seen many works of yours that are smaller in dimensions.

DS I like that size has to do with the relationship of the painting to the human body. I always like looking at paintings where you could come close enough to it so that you don't see anything around. You’re absorbed in the reality of the painting and it almost hugs you. Sometimes this may be horrifying, but I like the sensation when the reality of the painting is becoming unescapable.

JB Did Venice impact your work so far?

DS Maybe it's a bit too early to say. Some of my friends told me that I started using yellow more. But I don't know. It's hard to say so far. Maybe in a year or a couple of years, I will know. Who said that? I think it was George Condo… I keep quoting him for some reason… I mean, I don't even look at his paintings that much… He said, "You do things first and think later". So you kind of have to do stuff and then you go, Oh shit, it's interesting that I was influenced by that. And you sometimes don't even know what you were influenced by. But I do find the sky here to be very special. Especially from Giudecca. The way it changes within a 30 minute period. The color can completely change. So I think I'm learning. I'm learning color here, the color of the sky or the color of air.

JB As I was reading about you, there are these CV snippets that always mention your post-Soviet upbringing, although I didn't see in your work that you actively engage with it…

DS No, I don't think anybody mentioned it as a part of the work. It's the stuff people say about you, I really don't get involved. I mean, I don't do my own Instagram. You're here in my studio, in the world where I exist. I don't exist anywhere else. I just don't get involved with exhibition texts and whatever people say.

JB So you're not very concerned about your self-representation?

DS Well, if you're concerned with that, how do you have time to paint? I think when you're really an artist, you live in the service of the work. And so you have to cut yourself from a lot of concerns, or at least that's how I felt, that's what I had to do. At some point, you start selling your talent by thinking about stuff that doesn't really matter. I mean, who cares that somebody says one thing and the other person says another?

I don't come from a cultural background. I didn't know any contemporary art. I didn't know any art up until I was 16. I never saw a single exhibition in my life. I never did art, and then I started doing art. And up until I was 20 or 19 maybe, I’ve never seen a single painting past [Pablo] Picasso.

I think it was a friend of mine, Martin [Schlombs], who found my post-Soviet upbringing to be interesting, and so he wrote that text. And I think it was just used everywhere after that. We specifically had a show in Cologne of paintings where I would paint over [Georg] Baselitz prints, and I think Martin found that to be almost like a punk attitude where I don't care. And I was just so impressed with [Georg] Baselitz that I'm like, Oh, I'll just go and print that. So I think he related my post-Soviet upbringing to that kind of punk attitude where you were not exposed to anything. And now you discovered it as if it just happened yesterday. And so you don't have any baggage as you were asking, So what's your relationship to the history of oil painting? And I was never really concerned with these questions. I just approach everything as if Velázquez, a rag on the floor, or a condom exist exactly on the same hierarchy level. I feel free to sample and to take from things without any concern for their historical baggage.

JB That sounds like a musical approach…

DS Yeah, yeah, exactly. I actually used to do sampling, like beats and stuff like that…

JB Soundcloud?

DS No, no, I didn't, I never made a Soundcloud, gladly. I was very bad at it, but I liked the approach that you can use anything you see in the world. And speaking of music, I think Bob Dylan’s approach really influenced me. The way you listen to the lyrics and he just takes things and mixes [Queen] Jane with St. Augustine, just anything that's on your picture plane. So maybe if I'm trying to understand what my post-Soviet upbringing means, I think maybe that's what it might mean.

JB …so essentially punk? Untouched by all those influences?

DS You know, punk is again something that people say. For me, it's just life. Somebody might call it punk. But I’m not trying to be. I don't know how else to do it.

JB Coming back to that Georg Baselitz-inspired exhibit you mentioned earlier, there was a lot of violence in your works. I didn't see how you paint these works here, but the result looks similarly agressive, although it's really not the obvious theme. Would you say that violence is the right word to describe your process?

DS I think I want paintings to be somehow true to the way I understand life to be or the way I saw life to be so far. They have to be truthful somehow. So I think the truthfulness of paintings is what I'm really interested in. I mean, when you read [William] Shakespeare, is Shakespeare violent?

JB Partly…

DS Well, there we go. Like, life itself, you know? So it's not really something where I’m like, Oh, let me try and add some violence to the painting. You're just trying to paint something that feels true to life, to the things that are around you.

JB Are you more of a life optimist, realist, or pessimist? Or do you not think in such categories?

DS Daniel Kehlmann wrote this very sweet almost like a homage mentioning magical realism. It's realism that allows magic to happen. So I think that I'm a magical realist. There's always an opening for a miracle, you know? And that's a beautiful thing. Maybe the paintings can become almost like a… What do you call the thing you run on…? A treadmill, yeah. They become like a treadmill for your soul because they point you to a reality that allows magic. So somehow, it's always hopeful.

Art is always hopeful, even if the subject might be depressing. There was a great [Andrei] Tarkovsky quote. He said, “Art is a representation of life. Life has death in it. And a representation is a record that doesn't have death in it. So by default, it's optimistic.”

JB As a ‘95 kid you’re kind of in between generations. Would you rather say you’re Gen Z?

DS Look, I’ve never listened to anything but Bob Dylan. But wouldn’t it be great? To speak with like and you knows, and oh my gosh… What a fucking dream. I want to basically speak in a Gen Z way, but I don't know how.

JB Do you have TikTok? That would help you become more Gen Z…

DS Yeah, but I'm too judgmental. I'm a very judgmental person. Makes me wanna go you guys are stupid…

JB That’s actually how I feel reading a lot of exhibition texts, to be honest. I really hate it when they're like The artist is investigating the interconnection of human ambivalence through the sublime divinity of the painting through the real and the unreal, the conscious and the subconscious...

DS It reads like a joke that stopped being funny. Those are exactly the things that don't allow people to come and experience the work. It's almost like they turn things into a religion instead of an experience.

With any exhibition or artwork, if you need a text to experience it, I don't think the work is successful. My favorite art has always had a presence of its own. And it's that presence that defines the meaning of it. Not the intellectual background or whatever. Who cares what kind of research you did before making the artwork? If I don't see it, then why would I care? And I think it's very pretentious when artists do works and then they write huge texts because they could spend their time trying to make the work good instead of spending their time writing texts about it. And I think it's pretty offensive. It's pretty offensive to the art. It's pretty offensive to the public and to the viewers.

JB: Definitely. I’ve seen a lot of those exhibitions. What I'm really trying to do is write in a fun way, but also only write what I believe. If I don't see something in an artwork, I'm saying it, if I'm not convinced by something, I'm saying it, or if I see something, where's the evidence for what I found? I'm not trying to use any fancy words, like Look at me, I know how to speak English, right? I really just started it right now. I don't know how long I can keep this streak going before burning out. I don't know about you, but I'm always starting projects and then I leave them in the middle…

DS: Yeah. Sometimes. It used to happen to me a lot. I mean, it's still happening, but do you have anything better to do?

JB: I’d rather write…

DS: You know, that's beautiful. If you're doing something for people's response, you'll never get started with anything because nobody cares. But maybe if you care, you have already one person. Because otherwise, do you have anything better to do? If you think you have something to offer, then you’ve got to do it, for yourself, for everybody else, for us, for me… Even how this happened… You came up, you asked if we could do this interview. Nobody asked you to do it but you did it anyway. It's cool because most people don't really want anything from you. They don't want to engage.

JB: I think they're a bit scared. I was also scared, like, Can I just walk up to an artist like that?

DS: But that's okay, I mean, I went through a lot of these situations, too.

JB: …feeling a bit like an imposter…

DS: No, it's like 99% of the time. Yeah, I feel that a lot. But that's okay, that's how it feels to be making anything new.

JB: Sure. Fear of failure is pretty big…

DS: But failure doesn't exist… apparently. Somebody told me it doesn’t. Actually, I asked [Julian Schnabel] exactly the same thing. I asked him, “When you set out to do something, how do you do it? How do you fit the shoes?” He says, “Well, there's no failure. There's no failure.” And I'm like, That's beautiful. Somehow, it's true because it sounds right. But fuck, it's scary.

JB: Yeah, it's scary because I always think about What if they don't like you and that's it and they'll never look at your work again and then you can’t say, oh no, wait, I did better stuff now!

DS: But you can't control that. What’s your own relationship with that thing that you want to do? That's the only thing you're able to control, right? And sometimes you're not even controlling that, because control is also like a weird word…

Do I have paint on my face? I'm just realizing.

JB: On your head, but not on your face.

DS: Okay, good. Are you having a conversation with a moron?

JB: No, I mean, this is what I imagined an artist to look like, all in the material and the work…

DS: Fulfilling all the stereotypes.

JB: I mean, with the cigarettes and the music playing…

DS: A little pretense never hurt nobody. You know?

JB: You would need a turtleneck for the full picture… but rather for an exhibition opening…

DS: …yeah, I'm not sure if I would turn into that turtleneck type of artist. I know those, not fond of them. I like artists who walk around in the same stuff that they work in. I always thought that if a stock market person or a real estate person could go to a pub or to a social situation in his work clothes, why can't I?

Daniel Spivakov: A skull, a condom, and Velázquez is on view until November 16, 2023, at Stallmann Gallery, Berlin.

Stallmann

Schillerstrasse 70

10627 Berlin, DE

Free entry

Website

Thank you for showing me around, Daniel! I hope you guys enjoyed our convo. Leave me a comment with your thoughts, a like, or maybe you’ve got someone in mind who’d be interested in reading this review, too?

See you soon!!!

Jennifer

The Gen Z Art Critic